The material is a review on the work

Bjorn Lomborg. (2020). "Welfare in the 21st century: Increasing development, reducing inequality, the impact of climate change, and the cost of climate policies"

Currently the issue of global warming is associated with the concept of "global panic." Confirmation of this phenomenon can be found in the search results on Google.com when entering the keyword "Global warming." Over the past 5 years, the number of results in response to this keyword has increased by 2.5 times compared to the 20-year period before that. Society is deeply concerned about climate change, which is expected given the information environment in which modern society exists. Most news reports from the media link any extreme weather event, either directly or indirectly, to global warming.

Under constant pressure from the narrative that "climate change is the most dire threat to humanity," citizens of developed countries are demanding their leaders take measures to combat this alarming phenomenon. For instance, in 2019, 6 million people from all corners of the Earth participated in protests for various calls to action against global warming. There are other examples, such as when 30,000 "green" activists staged a rally in the United States in 2018, or thousands of protesters blocked five London bridges in the United Kingdom in the same year. In response to such mass demands, leaders of many countries and international institutions have announced their "costly" initiatives to address climate change. For example, the European Union plans to allocate €600 billion to achieve carbon neutrality (net-zero) by 2050 in accordance with the European Green Deal program. Additionally, the United States intends to provide over $500 billion for climate restoration over the next 10 years.

These staggering sums may provide reassurance to many, signaling that the world is now safe and ready to continue development. However, Bjørn Lomborg, the author of books on this topic and the recipient of numerous accolades, including recognition as one of the most influential thinkers by Time magazine in 2004, does not believe in the cost-effectiveness of such expenditures. In his scholarly article on global welfare in the 21st century, he asserts that such resource allocation is economically irrational. In his view, humanity would benefit more by spending less on addressing climate change and more on other societal sectors, such as global trade, healthcare, and so on.

It is important to note that the author acknowledges the looming danger of global warming, caused by human activity. However, he contends that the argument that global warming will lead to catastrophic consequences for humanity is mistaken. This is because this argument fails to account for crucial factors such as significant wealth growth, adaptation to external conditions, the relative economic damage, and overly ambitious goals in terms of reducing global warming to 2°C or 1.5°C.

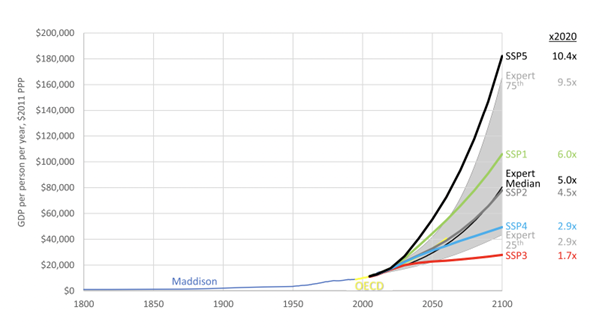

Commencing with a substantial upswing in the welfare of the global populace, the researcher presents a range of scenarios for the growth of the global GDP up to the year 2100. On the graph, the leading strategies are predicated on fossil fuel-driven development (UN, SSP5) and "sustainable development" (UN, SSP1). Nonetheless, the author underscores that the strategy referred to as the "Middle of the Road (SSP2)," projecting a GDP size exceeding that of 2010 by a factor of 4.5-5, aligns most closely with the consensus of experts. Additionally, the author, relying on authoritative sources, anticipates a significant decline in the level of inequality, which is expected to diminish more rapidly than it has increased over the past two decades. Ultimately, humanity is steadily progressing toward a substantial leap in wealth and a reduction in inequality.

Furthermore, building upon the increase in prosperity, Bjørn presents counterarguments to proponents of the idea of extremely high economic damages resulting from climate change. Supporters contend that rising sea levels, an increase in the frequency and severity of climate-related disasters will significantly impact the global economy. For instance, in the work by Jevrejeva et al. (2018), which has been cited by numerous media platforms worldwide (India Today, New Scientist, Axios, Science Daily), flood damages are estimated at $14 trillion annually by the year 2100. However, the researcher introduces authoritative sources indicating a long-term decline in the frequency of droughts and forest fires. Additionally, he highlights the lack of data and evidence concerning the global increase in flood frequencies. In Dr. Lomborg's view, such studies fail to account for a fundamental aspect of human nature - adaptation. The extent of economic damage will not be as high and will even decrease relatively. A significant portion of the "growing" damage disappears after inflation adjustments. Moreover, when compared to expected GDP levels, it turns out that the economic damage from climate-related disasters is decreasing, as it has over the past few decades. As an example of adaptation, the author cites coastal regions' administrations that continuously combat rising sea levels. The methods they employ include elevating port docks, building levees, and artificially raising the ground level in vulnerable areas. Japan, over several years, achieved impressive results by raising the height of several regions by 8 meters and elevating certain cities by 3 meters, protecting a total of 200 kilometers of coastline. Such solutions to protect countries from rising sea levels and associated losses require significant investments, and a country like Japan can afford such expenditures. However, considering the future manifold growth of global prosperity, a significantly larger number of countries will be able to finance the implementation of similar adaptation strategies.

Subsequently, the researcher delves into a discussion of the Paris Agreement. The author demonstrates how expensive it may be for the global economy to fulfill the commitments of the Paris Agreement. According to various forecasts, the required investments will reach at least $1 trillion by 2030 and could approach $2 trillion by 2050. As a result of such investments, it is expected that the Earth's temperature should decrease by at least 0.8°C, possibly even by 1.5°C. It is important to consider that the majority of countries, especially those responsible for the majority of CO2 emissions, are significantly lagging behind their commitments. Taking this into account, the author expresses doubts that leaders of countries will adhere to their promises, let alone increase investments in this direction in the future, at the expense of a significant portion of their state's GDP.

Furthermore, the author proceeds to compare the economic justification for spending on climate change mitigation with other alternatives. According to his calculations, with rational investments in climate and energy, one can yield approximately $10 for every $1 invested. However, this does not apply to the goal of reducing global temperatures by 2°C, which is expected to yield less than $1. At the same time, investments in other sectors have the potential to provide a substantial return on investment. For instance, investments in healthcare, including expanding population immunization, reducing tuberculosis deaths, and cutting malaria infections in half, could yield between $36 and $60. However, the most attractive investment would be the reduction of barriers to global trade, which could generate $2011. As a result, it can be concluded that there is no need to pursue lofty and unprofitable climate change goals when there are significantly more effective alternatives available.

Kazakhstan is also a part of the Paris Agreement, committing to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. Like many other nations, progress toward these goals has been slow. Furthermore, the government anticipates further growth in greenhouse gas emissions in the future. However, according to subsequent analysis by Bjorn Lomborg, it seems that Kazakhstan's lag may not be so critical. But, on the other side, the problems of the Aral Sea are manifested by long-term negative external consequences that were not observed at one time. In this regard, Lomborg's arguments can, in fact, also be tested today. Nevertheless, the work is interesting, at least, because of its attempt to shift the focus from the direct and low-return climate protection projects to the side of projects that can have indirect effect on the climate problem.