This article is a review of the study

Wang, D., Zhang, Q., & Yang, J. (2022). Higher education expansion and national savings level: Evidence from macro data. International Review of Economics & Finance, 82, 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2022.06.004

When uncertainty spikes, households save more. But what if upgrading skills changes that instinct? Wang et al. (2022) ask whether expanding higher education (HE) dampens national savings by lowering people’s fear of unemployment and nudging them toward consumption.

Empirical research by Wang et al. (2022) examines the relationship between higher education and national savings level, employing the system generalized method of moments (SYS-GMM) to analyze a panel dataset of 30 countries from 1991 to 2019. The authors conclude that the expansion of the higher education system is negatively related to the level of national savings, with a stronger effect in Asia and slightly larger effects in emerging economies.

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected the global economic order, increasing uncertainty and leading to frequent adjustments to fiscal, monetary, and education policies in many countries. Amid this uncertainty, as noted by Wang et al. (2022), precautionary savings have also gradually increased: in China the national savings rate was 45.7% in 2020, 1.5 percentage points higher than in 2019, corresponding to a global high.

In general, national savings levels have been studied through the lenses of pension system development, age structure, and precautionary motives. Wang et al. (2022) extend this body of knowledge by putting a human-capital channel at center stage and testing it across 30 countries. Theoretically, the analysis draws on precautionary-saving and human-capital theory. Amidst the current transformations in the higher education sector such as its internationalization, increase in autonomy of universities, digitalization and AI developments, it is especially interesting to assess how the sector can be related to the national savings.

On this basis, Wang et al. (2022) test the hypothesis that higher education expansion reduces the national savings level to some extent.

Empirically, Wang et al. (2022) investigate the relationship between higher education expansion and the national savings level. Higher education expansion level is depicted by the tertiary education enrollment level, which is the ratio of the number of students enrolled in tertiary education regardless of age to the population of the age group which officially corresponds to tertiary education (World Bank, n.d.). We therefore focus on youngsters studying in higher education institutions, universities.

Wang et al. (2022) regress national gross savings on the tertiary enrollment rate, controlling for inflation, the sex ratio, the non-agricultural employment rate, the total dependency ratio, levels of economic and financial development, and the real interest rate. Furthermore, the unemployment rate is considered as the intermediary mechanism and Baron and Kenny’s (1986, as cited in Wang et al., 2022) method is employed in testing the transmission mechanism of expansion in higher education on the level of national savings with the use of a recursive model.

Three main results were found based on examining data from 30 major economies including Russia, the United States and China:

A negative association between national savings level and higher education development level was found. A 10-percentage-point increase in tertiary enrollment is associated with roughly 0.3 percentage-points lower national saving.

The negative effects of higher education development on national savings are higher in Asian countries than in Europe and other regions. In emerging economies (Russia, India, China), the slightly stronger negative effect of higher education level was found compared to the global sample considered in the study.

Higher education expansion results in lower national savings by causing lower unemployment risks.

While the study’s contribution is to foreground a human-capital channel alongside the usual pension schemes or demography factors, endogeneity concerns remain since policy reforms and income growth can jointly drive higher education and savings level. Importantly, by raising lifetime income, higher education attainment can strengthen saving capacity, thus serving an important factor that we must not exclude in discussions.

Universal long-run prescription of the Wang et al.’s (2022) findings might not be fully plausible but understanding higher education as a component of sustainable growth and demand stabilization might lead further discussions and policy design. It proposes a new lens to consider national saving through the human-capital and precautionary-risk channels.

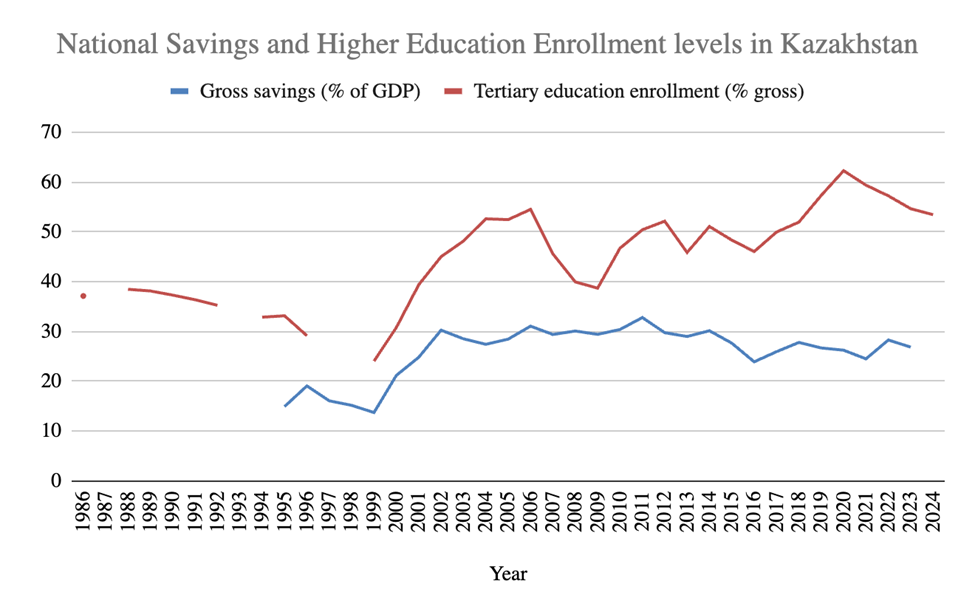

Applied to Kazakhstan, an initial visual assessment of the primary data was conducted to evaluate the strength of the human-capital channel.

Source: constructed by the author based on World Bank and BNS data

The graph depicts how the gross savings level relative to GDP and tertiary education enrollment co-move over the period. This visual representation of a rather positive relationship between two variables directs us to think of dominance of other factors in shaping national savings dynamics.

From the perspective of examining the relationship between higher education and savings through unemployment as the intermediary factor, being better-educated may not necessarily lower the risk of unemployment. Technological advancements and digital age development could reduce the relevance of university degrees (Beisembina, et al., 2025). As Beisembina and her colleagues (2025) note, “Kazakhstan’s education system does not keep pace with the labour market” (p. 4). Similarly, Sabirova et al. (2024) raised the urge to reorganize the education system based on the state of education and labor force qualifications in the labor market.

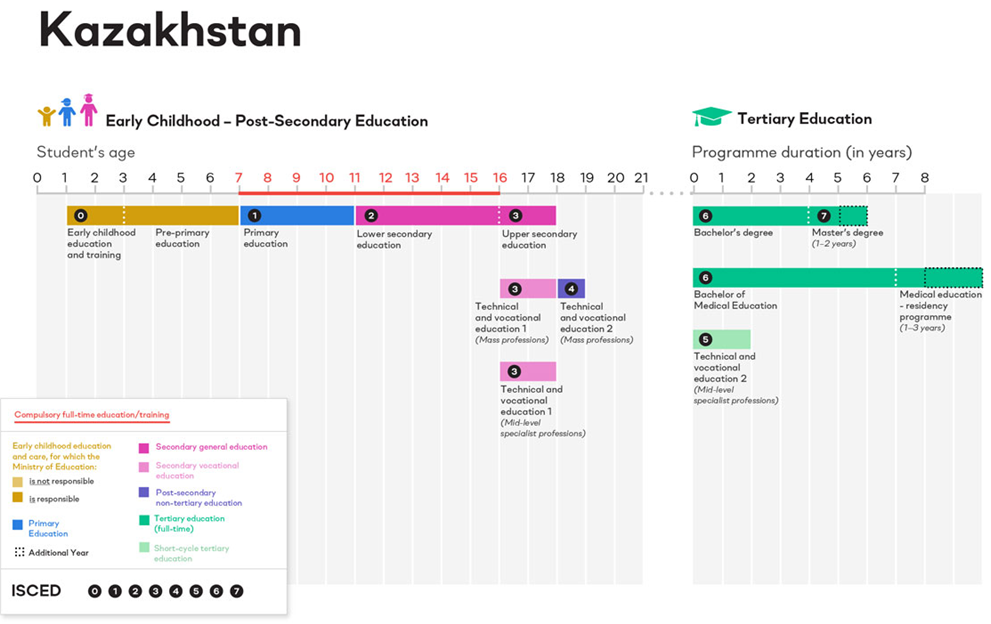

Source: UNESCO, ISCED Mappings and Diagrams: Kazakhstan

Importantly, the indicator of tertiary education enrollment in Kazakhstan does not include the youth in technical vocational education and training (TVET), in accordance with UNESCO’s ISCED classification. Empirical data suggests that TVET education in Kazakhstan provides students with practical skills, essential for their employability (Doskeyeva et al., 2024). According to the findings of our scholars, dual education in TVET institutions combining theory and practice provides youngsters with higher confidence in their demand in the labor market. In this regard, Khussainova et al. (2023) also noted that university graduates are more likely to be unemployed than TVET graduates.

While Wang et al. (2022) report a modest negative association between higher education expansion and national saving through precautionary mechanisms, our graph based on Kazakhstani data shows some positive co-movements between savings and tertiary education enrollment. This suggests that other macroeconomic factors play a more dominant role in determining savings levels in Kazakhstan, and the general assumption that higher education negatively affects savings does not hold universally. Interestingly, this raises the question of whether higher education in Kazakhstan enables graduates to meet labor market demands and, by increasing their confidence, reduces the need for precautionary savings. Overall, the mixed patterns in the data reflect complexities of the economic and social sector indicators.

Beisembina, A., Abuselidze, G., Nurmaganbetova, B., Kabakova, G., Makenova, A., & Nurgaliyeva, A. (2025). The Labour Market in Kazakhstan Under Conditions of Active Transformation of Their Economy. Economies, 13(5), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ economies13050131

Doskeyeva, G. Z., Kuzembekova, R. A., Umirzakov, S. Y., Beimisheva, A. S., & Salimbayeva, R. A. (2024). How Can Dual Education in Technical and Vocational Institutions Improve Students’ Academic Achievements and Mitigate Youth Unemployment in Kazakhstan. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 49(8), 516–531. https://doi-org.ezproxy.nu.edu.kz/10.1080/10668926.2023.2295472

Khussainova, Z., Gazizova, M., Abauova, G., Zhartay, Z., & Raikhanova, G. (2023). Problems of generating productive employment in the youth labor market as a dominant risk reduction factor for the NEET youth segment in Kazakhstan. Economies, 11(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11040116

Sabirova, R., Andabayeva, G., Mussayeva, A., Bissembiyeva, Z., Tazhidenova, A., & Karimbayeva, G. (2024). Development of human capital in the labor market in the modernization of the economy of Kazakhstan. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 18(4), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.14453/aabfj.v18i4.11

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (n.d.). ISCED mappings and diagrams. UIS. Retrieved November 17, 2025, from https://www.uis.unesco.org/en/methods-and-tools/isced/mapping-and-diagrams

Wang, D., Zhang, Q., & Yang, J. (2022). Higher education expansion and national savings level: Evidence from macro data. International Review of Economics & Finance, 82, 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2022.06.004

World Bank. (n.d.). Gross savings (% of GDP) – Kazakhstan [Data set]. World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNS.ICTR.ZS?locations=KZ

World Bank. (n.d.). School enrollment, tertiary (% gross) (SE.TER.ENRR) [Data set]. World Development Indicators. Retrieved October 8, 2025, from https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/world-development-indicators/series/SE.TER.ENRR

World Bank. (n.d.). Tertiary school enrollment, gross (%) – Kazakhstan [Data set]. World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.TER.ENRR?locations=KZ